Cloning Flappy Bird for the Nintendo 64 with libdragon (Part 1)

Yesterday I finally got around to releasing the source code to my “port” of Flappy Bird for the Nintendo 64, so I wanted to spend a little time to do a post-mortem on its development and look back on the bizarre phenomenon of Flappy Bird in general.

If you are solely interested in playing the ROM, you may be somewhat disappointed to find that it does not run in most N64 emulators. If you are interested as to why, the short answer is that most emulators don’t attempt to accurately represent the Nintendo 64 hardware. The best way to play this ROM is on a real N64 using a flash cart such as 64drive by retroactive or EverDrive-64 by krikzz.

This first part is an introduction into Flappy Bird and Nintendo 64 development to set the stage for a technical deep-dive of the source code. You can also skip ahead to the other posts in this series:

Flappy Bird for Nintendo 64 Project Site

- Introduction to Flappy Bird and N64 homebrew

- Starting an N64 homebrew project with

libdragon - Adapting Flappy Bird resources to

libdragonand the N64 hardware

Some context on Flappy Bird

On May 24 2013 a game called Flappy Bird was released for mobile phones by Dong Nguyen and quickly took the world by storm. While the game and its graphics were quite simple, its hook was remarkably effective: fly as far as you can, which is not quite as easy as it looks.

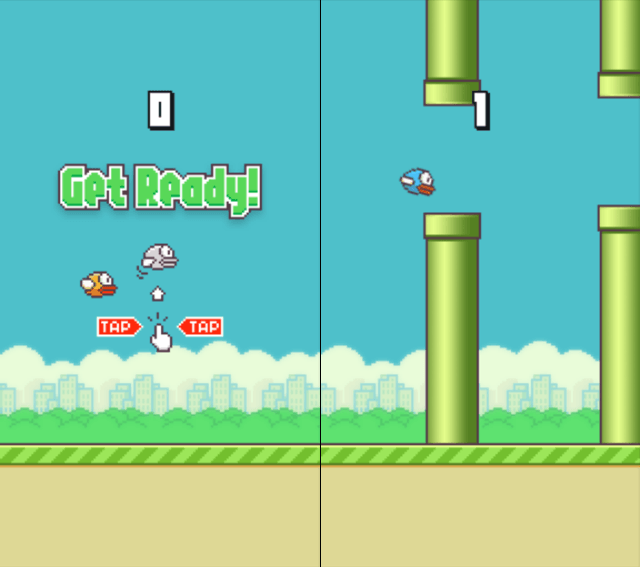

Objectively, you play as a bird who is constantly plummeting to the ground and must be kept aloft with continuous flapping to gain height. As you fly forward, you must navigate through narrow gaps between obstructions from above and below until you crash. The game is scored based on how many obstructions you clear, allowing you to compete for a high score and acquire medals for outstanding performance.

Due to its simplicity, a lot of people (myself included) looked at Flappy Bird and thought “oh, I could do that”. While the game lacks depth, it has a certain charm to it. Clearly it struck a chord with the zeitgeist of the internet, as innumerable clones and “rip-offs” of the game have been spawned since its creator removed the original from the App Store on February 10 2014. The “Flappy” game concept is even being used by Code.org as a tutorial aimed at teaching kids to learn programming.

Convergence with retrogaming

As a gaming enthusiast born in the 1980’s, I was quite delighted to see that there is a burgeoning scene of homebrew developers who have released versions of Flappy Bird for a wide variety of obsolete game consoles:

- Atari 2600 (Flappo Bird)

- Atari 2600 (Flappy)

- Commodore 64

- Dreamcast VMU

- Game Boy

- Game Boy Advance

- Intellivision (Flapee Bird)

- Nintendo Entertainment System

- SEGA Master System (Flip Flap)

- SuperGrafx

- Super Nintendo (Super Mario World Code Injection)

- Text Instruments TI-99/4A

- Vectrex (Veccy Bird)

- Virtual Boy (Flappy Cheep Cheep)

- ZX Spectrum

Right around the time of Flappy Bird’s rise to fame, I was going through an obsessive phase with my Nintendo 64 and started learning as much as I could about the technical aspects of the system. It only seemed natural that the N64 should be blessed by its own version of the smash arcade hit game of the year.

Software development kits

Out there on the internets you can find some amazing stuff. You can even find the official Nintendo Software Development Kit for the N64, which is proprietary, confidential, and disclosed only to official licensed developers. This is super neat, but Nintendo is renowned for aggressively enforcing their copyrights, so I ruled out using the official SDK that nearly all games officially published for the platform used. The fear of litigation has not stopped many other intrepid homebrew developers, so there is a guide available for getting started down that route (at least until the cease & desist letter shows up).

Since the N64 was developed and released during the mid-1990’s, much of the official tooling is still stuck in the past, having been designed around SGI workstations and Windows 95. I prefer not to use Windows whenever humanly possible, and trying to bring an SGI Indy back from the dead wasn’t something I had signed up for. What I was looking for was a modern toolchain that I could run on Linux and OS X. Luckily, such beasts also exist out there on the web.

Way back in 2005 a dedicated soul named Ryan Underwood (Halley’s Comet Software) took his vast knowledge of reverse-engineering the N64 and released the Open Source Nintendo Ultra64, a collection of tools and documentation for building N64 software without the secret Nintendo magic. This project appears to have been abandoned, but it was a fasinating resource and appears to have jump-started the N64 development scene. In 2009 Shaun Taylor (dragonminded) started the libdragon project, a library for interacting with the Nintendo 64 hardware on top of the GCC compiler suite and newlib embedded C library.

Ultimately, libdragon seemed up to the task, despite its work-in-progress status and limited feature-set compared to the commercial SDK. Controller input worked, 2D graphics rendered rectangles and sprites using both software and hardware-acceleration, audio output appeared to be possible with raw waveforms, and all of it seemed reasonably well-documented. Seeing the Yeti3D demo by ChillyWilly gave me hope that libdragon would be good enough for Flappy Bird.

Not using the commercial N64 SDK simultaneously liberated me from the tyranny of closed-source proprietary software, but also restricted the project with the severe caveat that most mature and popular N64 emulators won’t be able to run the game.

The mixed blessing of emulation accuracy

A physical Nintendo 64 performs general computation on the CPU, which is a pretty standard MIPS R4300i processor, and must be emulated in order to do much of anything. However, the CPU must go through the MCP (Master Control Program) RCP (Reality Co-Processor) in order to interact with the rest of the system. The CPU can off-load vector processing to the RSP (Reality Signal Processor) for high performance calculations performed by “microcode” instructions. Both the CPU and the RSP can generate commands for the RDP (Reality Display Processor) in the form of “display lists” which control its operating state to render shaded, textured, and depth-buffered geometry. The RCP is also responsible for communicating with the VI (Video Interface), AI (Audio Interface), PI (Peripheral Interface), SI (Serial Interface), and RDRAM (Rambus Dynamic Random Access Memory).

All of this means that in order to accurately emulate an N64, one must completely reverse-engineer the RCP, which is a massive and complex undertaking. There are only two emulators currently on the scene that even attempt this effort: CEN64 aims for perfect emulation down to the register-transfer level. MAME also intends for their Nintendo 64 driver to have low-level emulation accuracy. At the moment, neither of these emulators are as mature as the high-level emulation offerings, many of which sport extremely high compatibility with commercial N64 titles at full speed.

You may recall UltraHLE, the first successful N64 emulator, which was able to properly play a handful of real commercial games like Super Mario 64 and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time all the way back in 1999. UltraHLE took a different approach than other emulators of its day – rather than attempt to accurately mimic the hardware of the console, High-Level Emulation intercepts the C library calls to communicate with the hardware and emulates the library function without executing the low-level code that would run on real hardware. Even emulating hardware a generation older than the Nintendo 64 requires a significant amount of processing power to do accurately.

Since libdragon’s library does not even remotely resemble the official Nintendo SDK, emulators are not able to perform this high-level emulation with open-source homebrew and must accurately emulate the hardware in order to display graphics, play sound, and receive controller input correctly. This puts a small damper on the playability of anything made with libdragon for others, but as an N64 enthusiast armed with an EverDrive-64 I consider the real hardware to be the only target that matters.

Wrapping up

Now that we know what Flappy Bird is/was, have decided upon libdragon as our toolchain, and understand some of the limitations going into this, it’s time to get our tools situated and start building something. Read on to part 2 for a look into the technical details of setting up the toolchain and building an N64 ROM with libdragon.

Thanks for reading!